Imitation Crab Meat

By Adam Dudycha, Principal Industrial Designer

When someone views something on Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat, etc. they are usually only seeing the reworked, refined, over-edited, and filtered final version of that content. Very rarely do you see the “making of,” the failed attempts, the numerous hours of B-roll, or countless numbers of takes it took to get to that result. Not only does this hinder the process of trial-and-error and creativity by not seeing the failed attempts, it is also perpetuating the exact issue that’s causing the demise…”Here is a cool idea I came up with!” or “Check out what I made.” Only showing the final outcome falsely assumes that everything works the first time. Then, when someone attempts to recreate the result, the outcome can be, and is usually, dramatically different than what was expected.

When failure happens, one reverts to the comfort of the known. They revert to something that already works. Instead of learning from their mistakes and refining their direction and approach, creativity is stifled. The curiosity of what lies in that unknown arena is lost. I get it, I’ve done that before, and I regret not fighting through the failure. But, the times I do fight through it, with certainty, will always push my boundaries into the creative side of the unknown and let me dwell in the innovative, inventive “flow” that creative types long to reach. Failure is and can be, an option when creating. We should not be influenced by the negative connotation that the word “failure” invokes. Instead of “failing fast,” I like to think of it as “attempting aggressively!”

I was asked to try and put into words how I go about tackling a project. Asking someone with ADD to collect their thoughts and write about them is analogous to asking that same person to stand in the corner of a round room. Oh, and by the way, don’t look out the windows when you go past them. It’s an impossible task. You just keep going in circles without ever realizing that there aren’t any corners AND you just keep noticing all the squirrels that you weren’t supposed to be looking at outside. That is, until you notice all the birds in the tree. Then the hue of the tree being a shade slightly off this year’s Pantone color. As you look deeper into the tree and get mesmerized by the leaves dancing and moving almost in unison, you notice the tractor by the barn that vaguely looks like a Massey Ferguson you were checking out on an auction site a few days ago. So, as you’re searching for the site to visit again, you see an ad for some boots you were looking at earlier and decide to do some research on how to make your own boots. Eventually you end up on Amazon buying a carburetor rebuild kit for a generator you got from a friend for free. Totally forgetting the original reason you were in the room anyway. Hypothetically speaking of course, but I digress!

To be honest, I have no clue how to write about a process. Primarily because I don’t believe I have “a process”. Or do anything different than most people do for that matter. I look at the problem or task at hand, determine what a “successful” outcome looks like, and then get to work. The difference may be that I am ok with something not working right, especially right out of the gate. 9 times out of 10 it doesn’t. I don’t judge myself, worry about what others may be thinking, or assume I know how to do anything. I just want to try it. My curiosity is peaked every time I try to figure something out. How each nuance of a mechanism can work together harmoniously to complete an objective. Or how an aspect of something very simple can transform the outcome so dramatically.

Let’s take, for instance, a control switch/knob that I worked on a few years back. This was a quick, five-day design sprint that only needed some visual content to explain potential options to next-level decision-makers. However, in that short timeframe, I was able to create a working prototype as well for the project, which was used to solidify the design direction…all while the project lost 2 days due to the customer needing to present something at an impromptu meeting within the following few days.

Let me preface this first by saying that I didn’t create anything novel or revolutionary. I just combined different aspects of components that had features I felt embodied what that “successful” outcome could be.

A customer came to us with a control switch/knob that just didn’t “feel right” on their production unit. When you get into the realm of “feel right”, characteristics of that become very subjective. One person may think it’s good enough, yet another might think it’s lacking something. What I assume most can agree on though, is that there is a certain feel that denotes quality or robustness…a visceral feeling that you know is what you wanted without even knowing you wanted it. Another design requirement was to also have the center of this switch/knob hollow to allow for future additions of a touch control LCD. All of this while trying to stay within the form factor they already designed around and be more cost-effective to make. Pretty simple, right? Not quite! Sometimes, projects fall into this weird space of “the skies the limit… but within reason.” It’s a self-defeating argument. I’m allowed to be as creative as I want, but I must stay within the boundaries and be practical about it. Not quite the “sky high” arena I hoped I could play in.

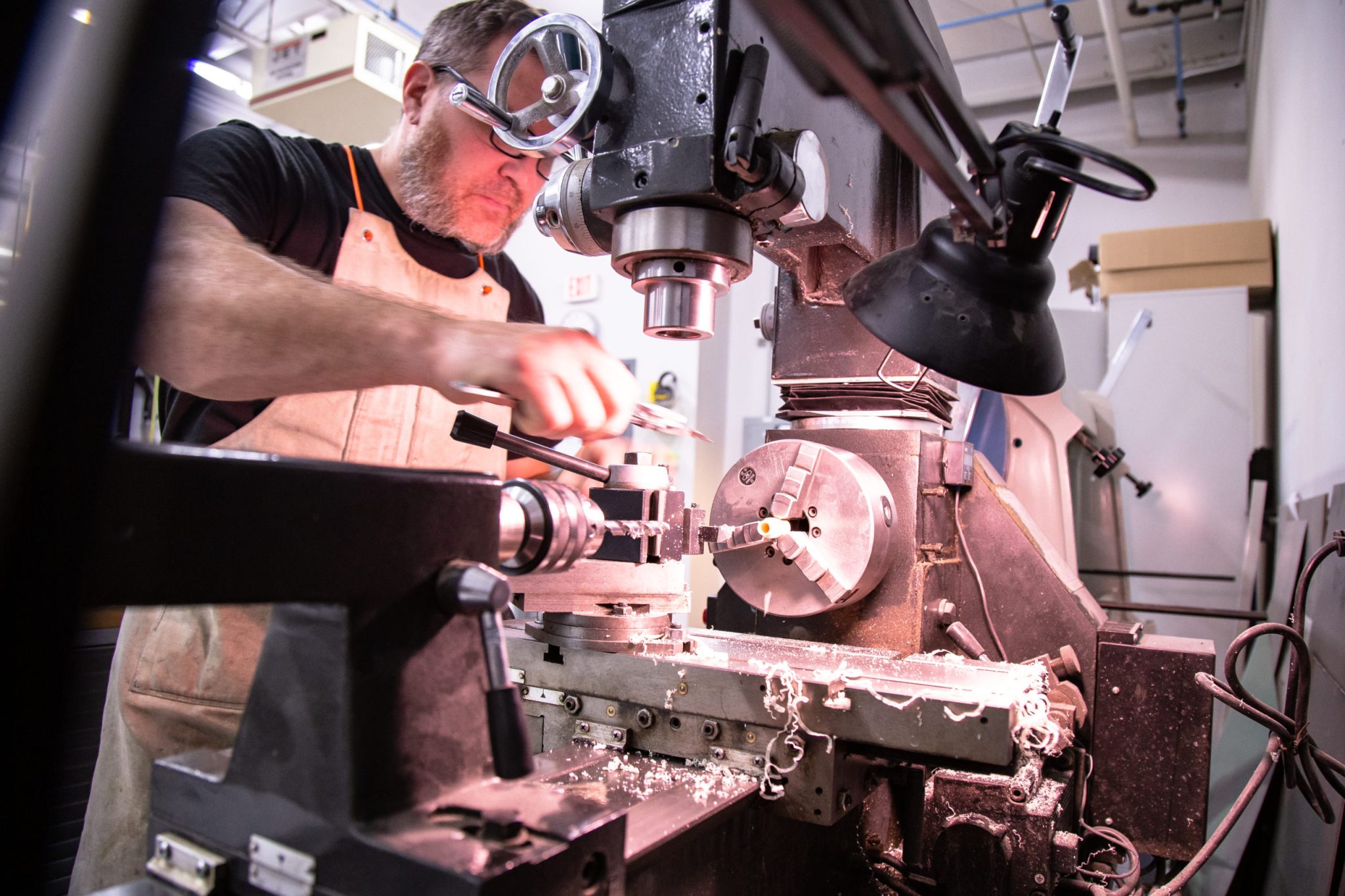

The knob they delivered had a cheap feeling to it. It had a lot of drag, the detents felt muddy and ambiguous. The finish was acceptable but lacked the quality one would expect from the name brand. On top of all that, some of the manufacturing processes of the components seemed bloated and unrequired. I dove in very quickly trying different approaches of how to create detents that felt good. Assuming most attempts would probably not work, I tried numerous ways of utilizing balls and springs, dampers, and fiction features that would coincide with where the detents needed to be. I built wood bucks and made 3D prints. I iterated quickly in CAD as well. Almost every attempt didn’t quite work the way I thought it might. The detent felt good but was too complicated to manufacture. The movement was smooth but lacked the detent required.

The stars would align, and different details would get me the desired effect but would be too obtrusive to fit in the space claim. This back-and-forth volley continued with every approach and iteration. However, one thing was happening in the process. Every failed attempt taught me something new to progress on. The feel of the spring, or the smoothness of the rotation. The simpleness of the detent interacting with the required movement. The solution was narrowing rapidly with every aggressive attempt but was just out of reach. I was missing something I thought should be simple. As the idea progressed, features of analogous products would spontaneously come into my head. Here is where my ADD helps sometimes!

“Best turnaround time on concept development I have seen in 25 years in this business, and you delivered three!”

I have taken quite a few things apart in my life to try and understand them. To try and glean some knowledge that was hidden from the typical use or to understand how these “things” work and, most importantly, how they work together. Those little nuances of mechanisms or assemblies that I spoke of earlier, I would bank and remember to use in the future. I remembered a rotary switch we used on a different project we had done a few years back. Specifically, how the detents were precise, crisp, and personified the “quality” feel the original knob was lacking. With tools in hand and plastic bits flying about, I was deep into the underbelly of the working mechanism.

One thing I want to note here is that we, as creative people, tend to believe that we have created something nobody has ever come up with before. We long for that one thing that will set us apart from the others. There are very few new and novel things being created to date. However, what is created and new is a way to package those novel ideas of yesteryear into new, exciting and unique ways. Don’t get me wrong, there is creativity there and I am not trying to take away from that, I am just stating that if you think something is new and unique, it probably isn’t. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to be novel in your approach; It just means somebody has probably already done something like it. Seeing what works and is successful is the sandbox I like to play in. I can iterate fast with the bank of knowledge that I have from assemblies and mechanisms seen in products past. What can I utilize that has already been done, but in a way that is new to what I am doing?

Inside that switch was a very clever answer to what I was looking for. Instead of a spring and ball nestling nicely into a groove (which, by the way, took up a tremendous amount of space but did give me the feel I wanted), several simple pieces of spring steel placed tangentially to the outer diameter of the knob at predetermined “bumps” would give me the feel, accuracy and space claim I needed. It was simple, customizable, manufacturable, and gave ample room to leave the center hollow…all while fitting into the confines of the space already allotted for it. This simple piece of spring steel also served as an automatic tolerance adjustment in both the assembly of the unit, and the potential wear accommodations that made the previous version feel sloppy and cheap. I took that idea and ran with it. Aggressively attempting new iterations of the “final” concept got me to a working prototype that was delivered and used to convey a new direction. That design also lent itself to two more ideas that were presented at the same time.

The customer was more than pleased with the results. One comment that validated the work, I felt was, “Best turnaround time on concept development I have seen in 25 years in this business, and you delivered three!” All because I tried numerous attempts at getting the knob to feel right. I didn’t just assume a direction was going to work and go down that path. The three-day project wouldn’t allow for that. If I attempted one direction and it failed to work, I would have missed the deadline. It took multiple tries and failure attempts to get to the result that fit the design criteria and worked.

This is just one of the many projects that I have had the privilege to work on in the 12 years I’ve worked at Tekna. Yet, it follows the same approach I take for most projects. I don’t think I do anything different than most people do when it comes to working on a project here. I think the difference might be that I am ok if the idea doesn’t work out the first time. In those failed attempts is where I find the answers most of the time. This process, if there is one there, is primarily the basis of how I tackle most projects. What have I seen in an analogous product that does something similar, and how can I get that to work within the boundaries I have set before me? Working within those boundaries is where failing fast/attempting aggressively creates the mindset to feel comfortable with whatever direction the attempts take me. In doing so, it inevitably advances the creative side where the development of products and solutions isn’t pigeon held to what we may think we are capable of.

So, to try and wrap up this rambling of a thought, enjoy the journey of exploration. Create as much unedited B-roll content as the project allows for. Utilize all the knowledge one gains from looking at other ideas and products that have been created and don’t be locked into the mindset that if your concept doesn’t work the first time it means you failed. It just means you attempted an idea that didn’t work for that specific circumstance.

I titled this write-up, “Imitation Crab Meat” primarily to find it easier on my desktop as I wrote it and to just give it a name. As I progressed further into writing it, I realized there is a correlation between the nomenclature used and the process of creativity I was tasked to discuss. Or, more so, how my process of creativity and curiosity melds together to take on a project.

Imitation crab meat, believe it or not, goes back hundreds of years to Japanese chefs looking for a way to use all the leftover fish bits cut from fillet – it is called surimi. Surimi is basically the way I go about designing new ideas and concepts. I take a little bit of this mechanism and a little bit of that assembly, smash it all together, add a little flavor, a little color, and package it up into something useful. Albeit it’s not in its original form, this mashup now takes the form of what it needs to be. It’s not really advanced development, it’s just imitation crab meat!